Wall Street had favoured Hillary Clinton, fearing Trump’s positions on trade. Markets settled down on the US open as investor fears of the most extreme policies abated.

Fast forward to 2024 and Trump has returned, with Republicans controlling the House and Senate on the back of a similar policy agenda centred around trade and immigration. This time, however, equities rallied prior to the election on expectation of a Trump win and post-election once his victory was confirmed.

The key difference between 2016 and 2024 is the state of the US balance sheet. In 2016, the debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio was 105 per cent, peaking at 132 per cent in the second quarter of 2020, and standing at 120 per cent today. The deficit in 2016 was 3 per cent of GDP, while in 2023, it was over 6 per cent, and according to Deutsche Bank, will average around 7 per cent over the Trump presidency, higher than the 6 per cent average projected by the Congressional Budget Office.

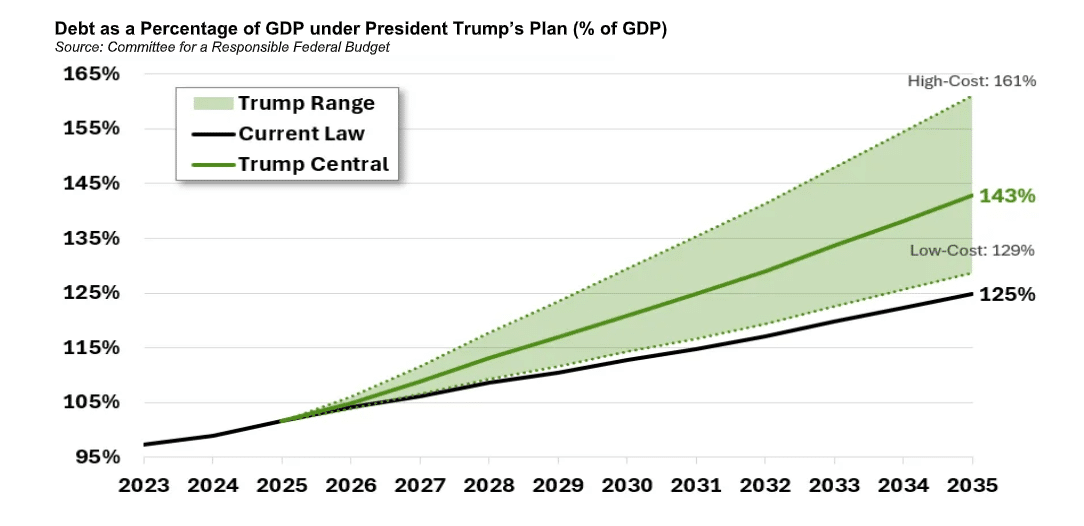

Prior to the election, the bipartisan committee for a responsible federal budget estimated that a Trump presidency would result in an 18 per cent increase in the public debt to GDP ratio relative to the current trajectory (note the below chart shows the debt held by the public and excludes debt held by federal trust funds and other government accounts).

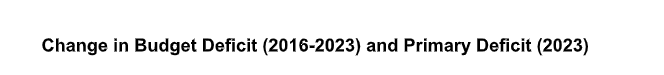

The problem for the United States is not so much the change in the deficit but that it is so much more than those observed by its peers. From 2016 to 2023, the debt to GDP in the United States increased by more than 15 per cent, second most of the peer group above. Perhaps even more concerningly, the primary deficit in 2023 was the worst among these nations, suggesting, if the above projections hold, the United States debt to GDP ratio will be the second highest among developed nations only trailing Japan.

Adding to the supply story is the demand side of the equation. During periods of quantitative easing, the Federal Reserve is a classic example of a price-insensitive buyer. However, since mid-2022, they have been a price-insensitive net seller (effectively, by not reinvesting principal repayments), with the balance sheet down by around US$0.75 trillion to US$7 trillion over the last 12 months. The Fed is currently allowing up to US$25 billion in Treasuries and up to US$35 billion in MBS to mature without reinvestment monthly, which could result in another $0.7 trillion reduction over 2025 i.e. a quantitative tightening period. Contrast to 2016 when there was virtually no change to the Fed balance sheet.

With the Federal Reserve out of the equation, the marginal buyers over the past 12 months have been largely price-sensitive buyers; money market funds (up US$1.2 trillion), private foreigners (up US$0.5 trillion), and households and non-profits (up $0.35 trillion). Commercial banks, a price-insensitive buyer, have increased their holdings, up US$0.15 trillion in the 12 months to 30 June 2024.

With supply increasing and the marginal buyer of treasuries transitioning from a price-insensitive one to a price-sensitive one, the bias would seem to be for yields to move higher. Of course, the Federal Reserve remains the buyer of last resort but, in all likelihood, will only step in where absolutely necessary. Markets are now pricing the Fed Funds rate declining to around 3.75 per cent by early 2026, a full 100 basis points higher than what was priced only two months ago.

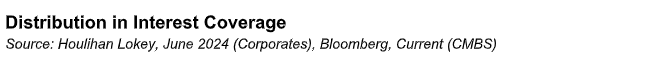

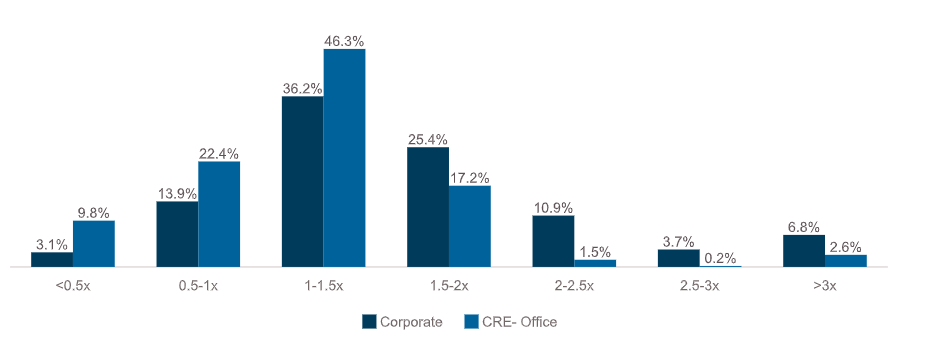

So, what does higher for longer mean for credit? For the most part, corporate credit has been resilient to higher interest rates and has weathered the hiking cycle well with higher earnings, muting the impact of higher interest rates. For the S&P 500, earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation has increased by 15 per cent from the point at which interest rates started increasing. For middle market borrowers, the effect has been even more pronounced, with earnings increasing by around 20 per cent over the corresponding period. Interest coverage has stabilised at around 1.5 times with around 15 per cent of borrowers with coverage of less than one times. This will improve as interest rates decline.

The problem child for credit markets remains commercial real estate markets which is most acutely impacted by higher interest rates. A Bloomberg search of adjustable-rate office loans contained in commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS) transactions shows that over three quarters currently have serviceability ratios of less than 1.5 times with one-third below one time.

It’s ironic given the Trump family made their name in commercial real estate that the sector we expect to be most impacted by his presidency is corporate real estate (CRE), but it is the one that is more leveraged to interest rates. And while wider equity markets have rallied strongly to the new administration, mortgage finance real estate investment trusts are flat for the month.

To be clear, our view is not that Trump’s election and the Republican sweep of the House and Senate will result in systemic issues within the Treasury market in the United States. We’re also not suggesting that treasuries now entail some level of credit risk given the increases in the debt to GDP ratio that we expect over the coming years. We would argue that tail risks have increased given the unpredictability of this administration compared to the more orthodox Biden administration, but our central position is that a Trump presidency cements the higher for longer thesis.

Pete Robinson, head of investment strategy, fixed income, Challenger Investment Management