Markowitz’s Modern Portfolio Theory, first published in a paper in 1952, showed how uncorrelated assets complement each other, lowering risk while at the same time increasing expected returns.

In the most basic sense, diversification is achieved by investing in different asset classes that are expected to have low correlation with one another – equities, bonds, real estate, and cash.

What drives that low correlation is the different primary risk that each asset class is exposed to. Investors are compensated with a “risk premium” over a reference rate – the so-called risk-free rate – for putting their money in a specific asset. For example, high yield bonds are exposed to a risk of default (a credit risk premium), government bonds to surprises in inflation or a government default (term premium), and equites to market risk (equity risk premium).

Rarely, but not never, do all these different risks occur at the same time.

When equity markets are underperforming, assets like cash and fixed income can compensate for some of those losses and buoy the overall return of a portfolio.

But what investors need to understand about the three risk premia mentioned above is that they all share an assumption that the risk-free rate ascribed is right at any given time. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Think back to 2022 and the shock the rise in central bank policy rates caused to both stocks and bonds and their risk-free rates for starters.

There are some types of risk premia that avoid reference to a risk-free rate. Volatility risk premium – the difference between the implied (or expected) volatility and the realised volatility of an asset – is one of these. The spread between implied and realised volatility is persistently positive over time and is driven by risk aversion.

Another late great economist – Daniel Kahneman, the co-author of Prospect Theory – is known for first spotting behavioural biases. He argues that people are risk averse i.e. we hate large losses more than we like large wins. And in order to avoid those large losses we will, on average, pay too much.

Everyday insurance is a good example of how the volatility risk premium and risk aversion work in practice. The price we pay for insurance to protect us from events that are unlikely – like breaking a leg from a jet ski fall in Bali – is higher than the probability weighted cost of treatment.

In other words, we overestimate how likely it is that we will get hurt or fall sick while on holiday (implied volatility) and therefore overpay for protection. The actual outcome (realised volatility) is, on average, more benign.

Of course, there are instances where the outcome is severe – a broken leg, an operation, a lengthy stay in a hospital bed and cancelled flights – and our insurance policy has served its purpose well. But such outcomes are few and far between.

This risk aversion behaviour makes insurance a very profitable industry that generated $225 billion in profits in the past 12 months alone.

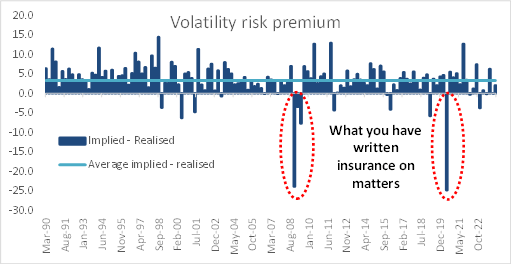

Historical analysis supports the benefits for investors of looking at volatility risk premium. Looking at the quarterly volatility risk premium since 1990, implied volatility, as measured by the VIX index, has been consistently higher than the actual realised volatility with a median gap of around 350 basis points.

Out of 137 quarters, the premium has turned materially negative only 11 times, usually when the markets are undergoing severe stress like the dot.com bust in 2000, the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Outside of these 11 quarters, the volatility risk premium averaged around 430 basis points.

Investors would do well to consider the additional diversification benefits of exposure to volatility risk premium, something we do in our funds at Talaria. Returns can be found by exploiting the persistence of a volatility risk premium (investors’ aversion to losses and their willingness to overpay for protection) by selling insurance (cash backed put options) on collateral we like (the companies we buy).

The volatility risk premium has very low to negative correlation with other types of risk premia, like equity risk premium, and offers uncorrelated returns ideal for building a well-diversified portfolio.

Hugh Selby-Smith, co-CIO of Talaria Capital