Former RBA governor Philip Lowe suggested the Australian economy could remain “on an even keel … but the path to achieving a soft landing remains a narrow one”. But an even keel on a narrow path sounds like we’ve already run aground. So, should you bet on a recession?

There’s nothing ‘technical’ about a ‘technical recession’

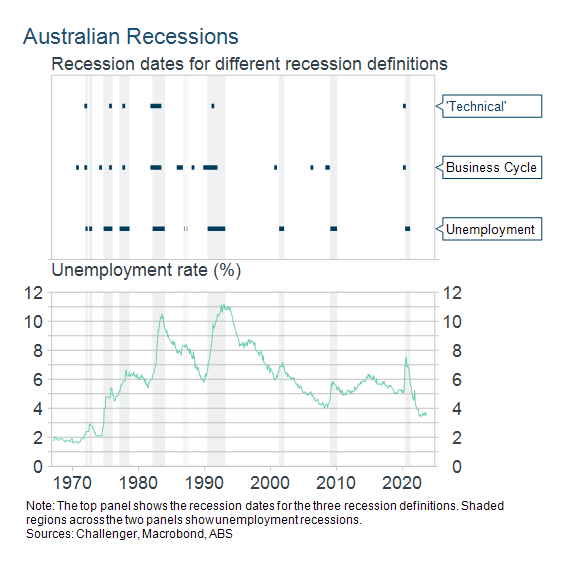

A frequently used (but arbitrary) shorthand is that two consecutive quarters of falls in GDP is a “technical recession”. But this simplistic definition is often misleading about recessions as discussed below.

In the US, the impressively titled National Bureau of Economic Research’s “Business Cycle Dating Committee” dates when recessions occurred. They determine the timing of recessions based on range of monthly data (income, employment, consumption, retail sales and industrial production). Two of the eight members joined when it was formed in 1978, so they’ve certainly seen a few business cycles!

Dating recessions in Australia

Even without a panel of esteemed academics, we can still do better than the crude rule of two negative quarters of growth. There are a couple of sensible alternative definitions.

- The first is to identify peaks and troughs in the business cycle using an algorithm applied to the level of per capita GDP (per person better captures people’s standard of living). This shows there were three recessions in the 2000s. Australia’s claim to 29 years without a recession doesn’t stack up. This method also shows the early 1990s recession lasted nine quarters, much longer than the “technical” recession definition. Anyone who lived through that recession knows it was long and deep. By this definition, Australia is currently in recession, with GDP per capita having fallen slightly over the first half of this year. However, past GDP growth and even population growth are often revised as we get more accurate data, and so our current business cycle recession could always be “revised away”.

- A second alternative is to date recessions with the unemployment rate. We care about the effects of recessions on people and job losses are the most tangible impact. A widely used option is the “Sahm rule”, which says a recession is when the (three-month average) of the unemployment rate has increased by half a percentage point in a year.

Both alternative definitions of recessions have advantages. The business cycle definition produces much more intuitive dating and lengths for recessions and it is still based on aggregate output (i.e. GDP). The unemployment definition is simpler and it is much more timely. There is always a long lag in dating a recession with GDP, we need two quarters of GDP and GDP is published with a significant lag. Recession can even be over before we can even say for certain that it started! By contrast, employment data are published monthly and with less lag. So, the unemployment definition will tell us we’re in a recession sooner, even if employment growth tends to lag GDP growth.

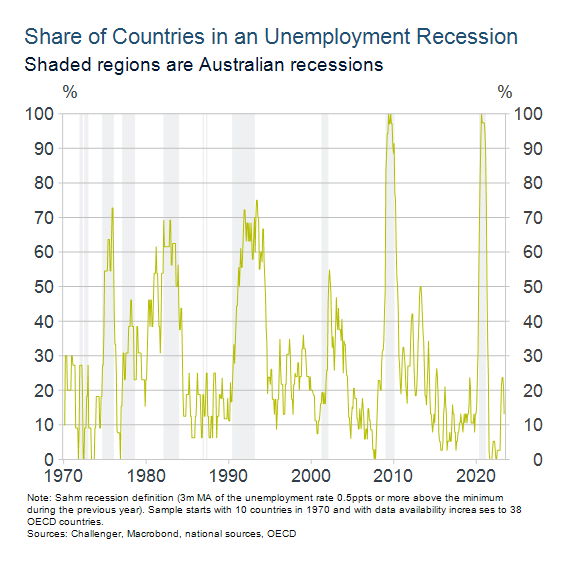

Recessions across countries

Countries often experience recessions at the same time. This can be because of common shocks, say the 1970s oil price shock or the 2008 financial crisis. Also, downturns in large economies spill over to others through trade and investment flows or confidence effects. For many years it’s been said that when the US sneezes, Australia catches a cold. Since the 1980s, every recession in Australia has occurred when half or more of other countries are also in recession.

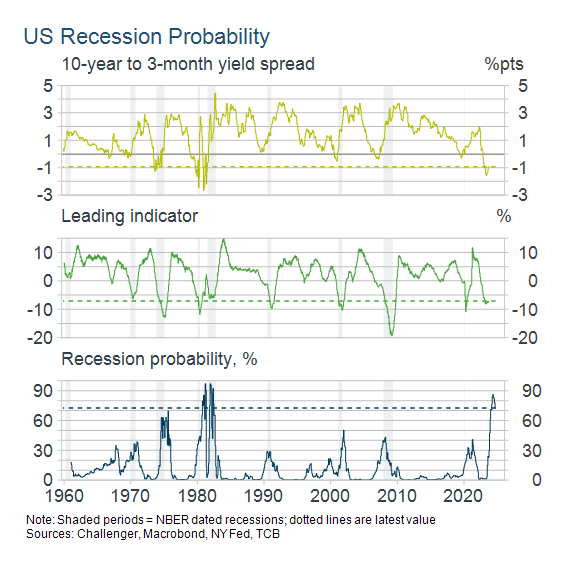

The probability of a US recession

The slope of the yield curve (the 10-year interest rate minus the three-month interest rate) has been shown to be a good predicter of US recessions. Each of the past eight recessions were preceded by an inversion of the yield curve, on average, around 10 months earlier. Recessions often follow a big increase in the Fed Funds rate, while prospects of future lower growth and interest rate cuts result in lower long-term interest rates. All US recessions have been preceded by short-term interest rates that are high relative to long-term rates.

Leading indicators – combinations of forward-looking economic and financial series (such as orders for goods, building permits, and equity prices and bond yields) – are another useful predictor of recessions.

Both the yield spread and a high-profile leading indicator are at levels only previously seen in or preceding recessions. A statistical model based on the yield spread suggests the probability of a US recession in one year is 55 per cent. Adding in the leading indicator pushes that up to 72 per cent, although this has declined from 86 per cent in May. More commentators might be backing a soft landing for the US economy, but if you back the models, you’d still put your money on a recession.

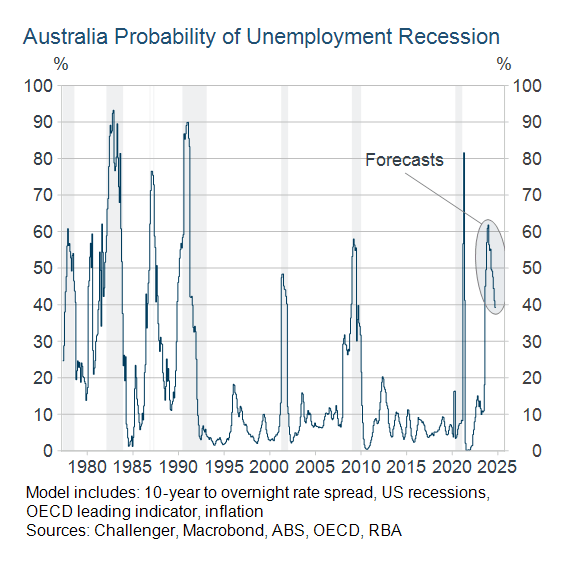

The probability of an Australian recession

We can estimate the likelihood of a recession in Australia using the slope of the yield curve (10-year minus three-month or overnight interest rates) and the OECD leading indicator (which comprises construction approvals, manufacturing surveys, share price index, terms of trade, and 10-year bond yield). High inflation or very low unemployment can also suggest a recession is brewing.

Our statistical model indicates that the probability of a recession in Australia in one year is 39 per cent (using the unemployment definition). Using the “business cycle” definition, it’s even higher at 60 per cent. But whether Australia does have a recession is likely to depend on whether the US does. If the US does experience a recession, then there’s a two-thirds chance Australia has a recession, but if the US sails through then the odds of an Australian recession are closer to one-in-three.

Not all recessions are equal

While based on GDP per capita, we’re already in recession, it’s important to note that not all recessions are equal. The early 1980s recession saw the unemployment rate rise 4 percentage points while it “only” increased by around 1½ percentage points in the 2008 GFC recession.

One area that has been highlighted as a potential risk in Australia is the high level of household debt. We’re a world leader in that race. At almost 190 per cent of income, our household debt is more than two-and-a-half times as large as in the 1990s deep recession. But from what we know, those households that owe debt are mostly well placed to meet their payment obligations. It’s likely that highly indebted households will significantly cut consumption in a recession, but I don’t expect that will be enough to turn a mild recession into something much deeper.

Overall, I think there is a good chance that we’ll end up looking back on the current period and seeing that we experienced a mild recession.

Jonathan Kearns, chief economist, Challenger