However, the composition of the index yield should raise alarm bells at present. The three iron ore stocks are contributing 31 per cent of the consensus dividends across the market and the four banks a further 26 per cent, so 57 per cent from just seven stocks in only two industries.

As we have seen, these are highly macro sensitive sectors with external influences outside their control determining most of their dividends. To illustrate this, banks contributed 41 per cent of the index yield five years ago and only 26 per cent today, which failed to foresee the impact even a short shallow recession due to COVID-19 would have on their dividends. In contrast, contribution from iron ore stocks has risen from 3 per cent to 31 per cent of index dividends over the same period, all on account of the massive recent rises we have seen in iron ore prices.

Iron ore earnings and dividends appear unsustainably high

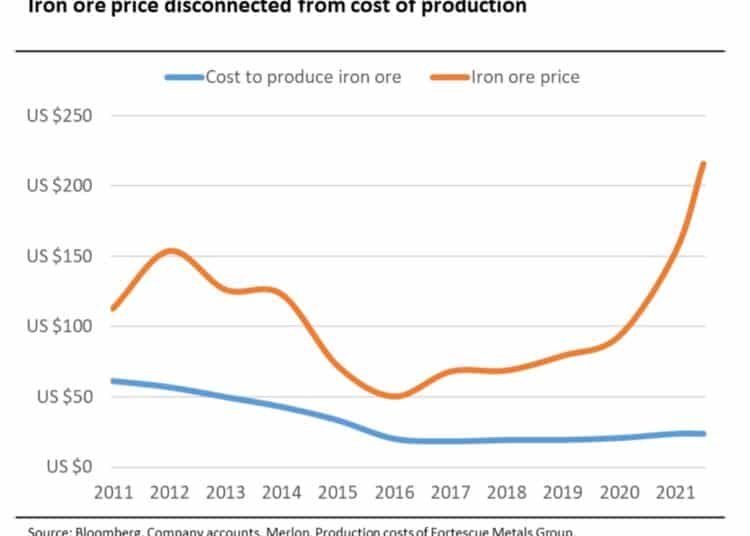

The chart below compares the iron ore price to the cost of production. Typically, commodity prices revert to the cost of marginal production as new supply comes on stream and there is little to differentiate the product – hence the term “commodity”.

In this case, we are charting Fortescue Metals (FMG)’s cost of production as the marginal producer. We must also give credit to all three Australian major iron ore producers for their excellent job in reducing costs and remaining disciplined on capital expenditure, which is different to prior cycles for now.

However, the fact the iron ore price is roughly eight times FMG’s cost of production highlights risks to the current spot price.

The price could fall when additional supply comes on stream, whether it be from Australia, or Brazil which has been plagued by mine disasters and the pandemic, or if Chinese demand moderates. Iron ore is a primary ingredient in steel-making and it is worth noting 5-10 per cent of Chinese steel production is exported – meaning that the domestic Chinese demand for steel for construction and infrastructure is what matters.

Furthermore, China is also under pressure to reduce its carbon footprint. All other developed economies have transitioned from manufacturing steel using blast furnaces to recycling steel as the economy matures – over two-thirds of US steel is recycled compared with just 10 per cent in China. We expect China to be no different although timing is difficult to predict.

All up it points to downside risk to the current price and even the Australian government Treasury Department is factoring $55 billion into its budget estimates.

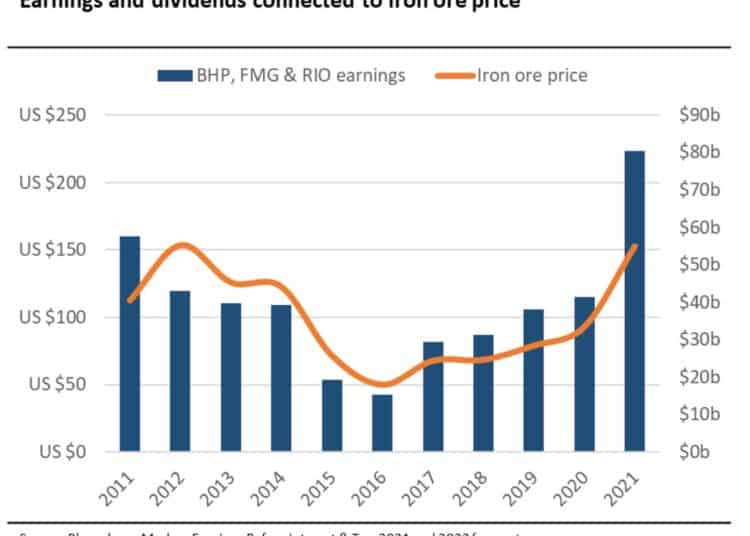

The next chart below repeats the iron ore price and highlights the substantial leverage the three iron ore majors have had to their earnings and dividends, and the risk if the iron ore price falls.

Their share prices are anticipating some decline in the price, but we still believe it will be difficult to preserve capital when the price falls.

We do not currently hold iron ore stocks to generate sustainable yield and capital preservation.

Bank dividends inextricably linked to the economy

At Merlon, we have always liked Australian banks due to their oligopolistic industry structure.

They continue to surprise us with their ability and willingness to reprice mortgages but have really surprised us in the way they have cut term deposit rates close to zero to protect earnings over the past year.

To illustrate this, the spread between a typical mortgage and deposit is now 2.5 per cent compared to 1-1.5 per cent average over the past decade. Credit growth is also recovering strongly, with housing finance approvals running at $20-$25 billion a month compared to $10-$15 billion in the decade prior to COVID.

However, they are riskier than perceived. The biggest driver of bad debts, and thus bank earnings and dividends, is the unemployment rate. To illustrate, if bad debts go from 0.3 per cent to 1.0 per cent of loans on average across the sector, earnings could drop 50 per cent and dividends would be suspended.

Of course, that risk seems a distant memory now with unemployment below pre-COVID levels but the risk of complacency is rising given fiscal and monetary stimulus will fade over time and impact of the current Delta COVID wave and lockdowns is still to be seen.

We believe Westpac offers the best risk-adjusted prospects out of the Australian banks, as it has the lowest expectations being priced into the share price at the moment and therefore less downside if things go wrong again.

Retail booming unless you are a tour operator or restaurateur

Retailers are enjoying a temporary benefit from closed borders and government stimulus, with the earnings for the large, listed retailers up more than 50 per cent this year.

We have found over the years the market treats retailers too harshly as cyclicals when many are market leaders in their respective categories.

We think the best exposures in the sector are Harvey Norman, Super Retail Group (owner of brands like Rebel Sport and Supercheap Auto), as well as Coles and Metcash (IGA supermarkets franchisee).

Whilst we expect earnings and dividends to fall, the good news is this is mostly already reflected in their share prices, providing downside protection. All of these companies trade at much cheaper earnings multiples than the broader market.

Furthermore, ongoing lockdowns might prolong the sales boost and the cash flows are paying down debt, which is just as valuable as dividends.

Neil Margolis, lead portfolio manager, Merlon Capital