This advice can be applied to many fields. Investment is one of them. It is well known that investors tend to chase returns by buying more of a stock or fund that has performed well, and vice versa.

For a bond investor, skating to where the puck has already been is a problematic approach.

Bond investors also tend to chase returns by increasing the risk they take to maintain or increase their yield. For investors relying on bonds as a source of income, there are now two choices: accept a reduced income or take more risk to maintain current income levels. Most do the latter, and time and time again at Daintree we see bond portfolios that investors believe to be defensive that are anything but.

Chasing returns in bonds is a bad idea; but chasing yield can make a bad idea worse.

Chasing returns

Most of the time, the return in the next quarter is lower, not higher, than the return earned in the current quarter. In other words, investors should not focus on where the puck has been, but on where it is going to be! Doing otherwise will destroy wealth.

For an investor holding a bond from issue to maturity, returns are wholly dependent on the interest that the issuer promises to pay. Any increase in the price of a bond will be fleeting. There are two implications of this:

- If bond yields fall (as prices rise), future returns will be lower as income is re-invested at lower yields.

- Whilst there is no prospect of a permanent capital uplift if an investor buys a bond at issue and holds to maturity, there is a prospect of permanent capital loss! A bond issuer may decide to not return investors’ principal, defaulting on their obligation to pay. This is credit risk.

Chasing yield

Playing defence in ice hockey can be really challenging. A flat-footed defence player will not be successful.

Bonds are an important defence to a diversified investment portfolio, and a portfolio without defence is one that is prone to large losses. With that in mind, we now turn to the relationship between credit risk and returns.

Of course, as is the case for any investment risk, there can be pitfalls for investors who chase yield and bias their portfolios too far down the credit risk spectrum. By doing so, such investors increase the potential for both increased portfolio volatility and loss of capital.

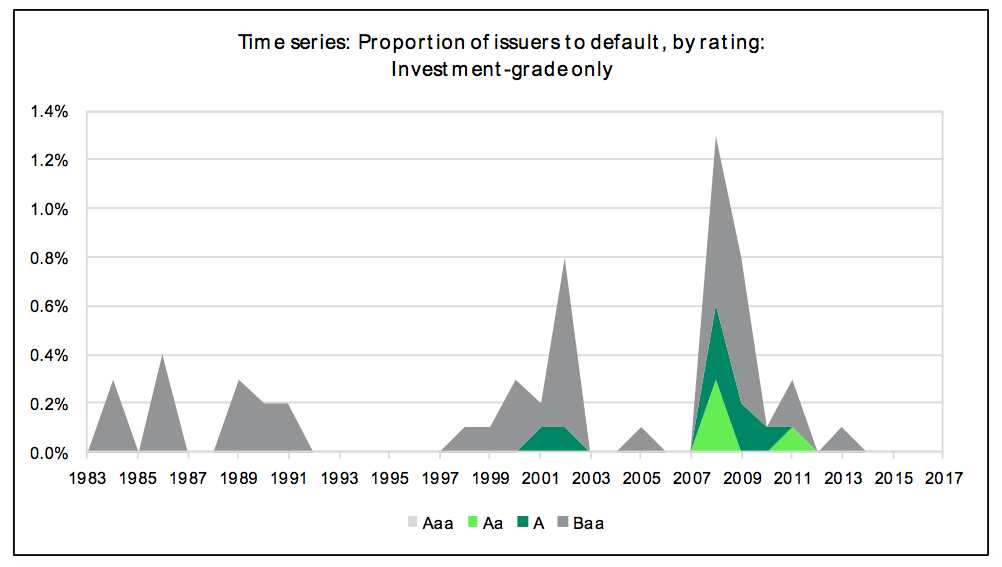

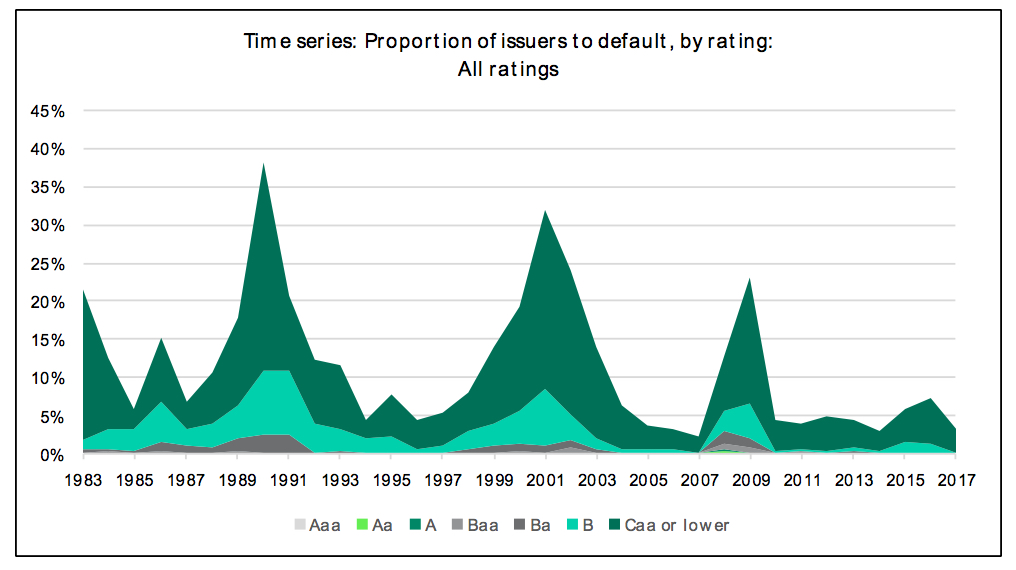

The charts below show the implications of taking too much credit risk in a bond portfolio. The default frequency of bonds globally is shown over time, grouped by credit rating, as measured by the credit rating agency Moody’s. The higher the default frequency, the greater the number of companies that did not remit interest or return investor capital in full:

Source: Moody’s Investor Service Annual Default Study: Corporate Default and Recovery Rates, 1920 - 2017

We can make two points:

- Defaults happen during and following stressful periods for markets: The 1990-1991 recession, the tech bubble of 2000 and the 2008-09 financial crisis all saw pickups in the rate of defaults, across both investment grade and sub-investment grade issuers.

- Defaults are much more prevalent among sub-investment grade issuers: Sub-investment grade issuers experience default much more frequently than investment grade issuers.

These are the pitfalls of investing solely for yield. Permanent capital losses can occur and are more likely to occur when other assets in a portfolio are also underperforming due to a weak economic environment. But even if there is ultimately no permanent loss of capital, credit investors can face volatility.

Chasing yield is like a team with no defence – heavy losses are inevitable at some point.

Conclusion

Credit investing should be undertaken with clear advice, active management and sensible diversification; otherwise, significant losses can occur at the same times that growth asset returns elsewhere in a portfolio are also falling.

Higher credit risk portfolios will exhibit greater volatility in good times and could suffer materially worse performance in bad times. This is the investing equivalent of skating to where the puck has been in a team with nobody playing defense. The result is going to be heavy losses that start from early in the game and get worse from there.

Our view is that fixed income portfolios should be managed by taking only the necessary amount of risk to achieve sensible return objectives, because the defensive characteristics that investors typically seek may otherwise by compromised.

Justin Tyler is director, portfolio manager – interest rates and currency at Daintree Capital.