Instead of panicking, however, we think investors should take a moment to understand the risks, so that they can make better decisions about what action to take.

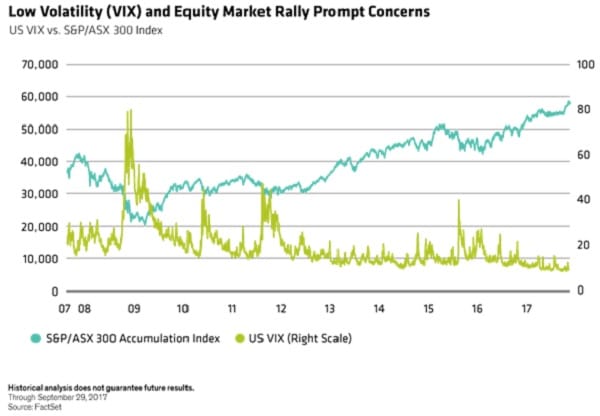

The most obvious clue that equities could be due for a fall is that, despite an environment of increasing macro uncertainty, market volatility has fallen to what appear to be unsustainably low levels (see chart below).

Since its low point in 2009 following the financial crisis to 31 October 2017, the S&P/ASX 300 Accumulation Index has rallied 172.1 per cent while the US Volatility Index or VIX has fallen to 11.28 – close to its all-time low.

In market lore, when the VIX is high it’s known as the ‘fear index’; when it’s low, it’s the ‘complacency index’.

On that basis, equity markets seem very complacent indeed. One explanation may be that investors are focused on signs of improvement in the US economy and elsewhere, and paying less attention to possible macroeconomic and market risks.

It’s notoriously difficult to predict when market corrections might happen, but we can identify what might cause them.

Five types of risk

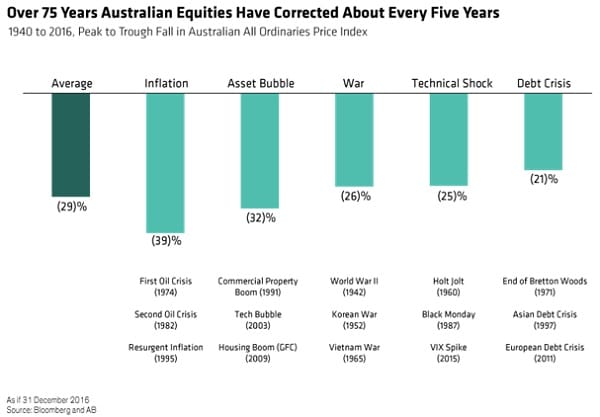

History can be helpful here. Our research shows that, over the last 75 years or so, the Australian All Ordinaries Price Index has had a correction about every five years on average, with the average size of the corrections being about 29 per cent (see chart below).

The last setback, caused by a technical blip in the VIX, was two years ago.

If we group these incidents by what caused them, they fall into five categories. Inflation has accounted for the biggest drop in the market on average during this period (39 per cent) followed by asset bubbles, wars, technical shocks and debt crises. How likely are they to trigger a market correction today?

Inflation is the least likely, in our view, because it remains low with little sign of upward pressure on wages. If, however, currency weakness leads to Australia importing inflation, the Reserve Bank of Australia might be forced to raise interest rates before the economy has strengthened sufficiently.

That would be painful for Australian equities.

The second biggest risk category, asset bubbles, seems likelier. Previous bubbles in Australia included the commercial property and technology booms, which ended in 1991 and 2003, respectively. Since 2009, Australia has been experiencing a boom in residential housing that may have peaked. A downturn would hurt shares in property companies and banks.

War and geopolitical tensions are also a credible, if slightly more remote, threat, given tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran, the US and North Korea, and between China and neighbouring countries over its territorial claims in the South China Sea.

The last time conflict caused a correction in the Australian market was when the country sent more troops to Vietnam in 1965.

Technical shocks are caused by changes in trading dynamics rather than stock fundamentals, and it’s not difficult to imagine such an event now if, for example, investors suddenly become nervous about the disparity between equity valuations and volatility and start to sell.

A related risk is the potential for program trading to turn a small sell-off into a large one.

Finally, debt crises. The 2011 European debt crisis is still fresh in many people’s minds and potential flashpoints for such an event today are central bank balance sheets and China.

One effect of central banks’ purchases of government bonds since the financial crisis has been to drive yields on those bonds to historic lows.

As the central banks prepare to reduce their bond holdings, yields are likely to rise again.

We expect the process to be gradual but, if central banks overplay their hand and force yields to rise quickly, they could trigger market volatility.

In China, where a government economic stimulus package caused a surge in investment-led growth after 2009, total debt appears to be uncomfortably high at nearly three times annual output.

This situation is made riskier by the fact that the provision of credit is now much more fragmented and increasingly reliant on a range of wealth management services rather than the banks, which were the main lenders a decade ago.

So, of the five risks that have contributed most to Australian stock market corrections in the last 75 years, four are causing warning lights to flash. What should investors do?

Think beyond quick fixes

Firstly, they should avoid complacency. Australia’s last recession was in 1991, a record 26 years ago. The average of share market corrections since then has been 22 per cent, which may seem better than 29 per cent over 75 years. This may not be the right way of looking at the data, however.

It ignores the fact that corrections for the previous 50 recession-prone years averaged 33 per cent. It’s possible that, if Australia’s unusually long recession-free period is about to end, the size of the next equity market correction could be more in line with those of the pre-1991 years.

Secondly, investors should consider stress-testing their portfolios as soon as possible. One way to do this is through scenario analysis, using the kind of risks we’ve outlined above.

How well would their portfolios perform if one or more of these risks caused a correction?

Thirdly, they need to understand that corrections can happen in different ways. In a ‘flash crash’, for example, the market falls sharply and quickly.

A bear market tends to grind downwards over months, or even years. Then there is the ‘false rally’, where a short dip is followed by a recovery, only to be followed by a deeper and longer downturn.

Given the potential uncertainties about the shape and scale of a correction, investors should be cautious about resorting to quick fixes such as moving into cash or buying derivatives – short-term measures that may turn out to be mistaken and, ultimately, costly.

A better approach, in our view, is to invest in a strategy that inherently limits a portfolio’s exposure to market downturns (by, say, 50 per cent) while enabling it to participate substantially in any recovery (up to 80 per cent).

By focusing on reducing downside, investors can have a smoother ride and still achieve the equity returns they seek. This can be achieved with a diversified portfolio of quality, low-volatility stocks.

Roy Maslen is chief investment officer, Australian equities at AllianceBernstein.