Clients often ask us when is the right time to invest in emerging market debt. In other words, they are asking if they can time the market. Our analysis shows the answer is no.

We found that applying a market timing strategy, which enters the market on dips, lags the returns of the index by a long way.

The Achilles heel of the strategy is that it spends too much time out of the market, and as a result, misses out on incremental market growth.

For investors, the best approach is to stay in the market and allocate within it.

Crunching the numbers

We evaluated a strategy that buys emerging market debt (EMD) in hard currency only after prices fall by a certain margin.

When prices recover sufficiently, the strategy switches back into cash until prices fall again and so on.

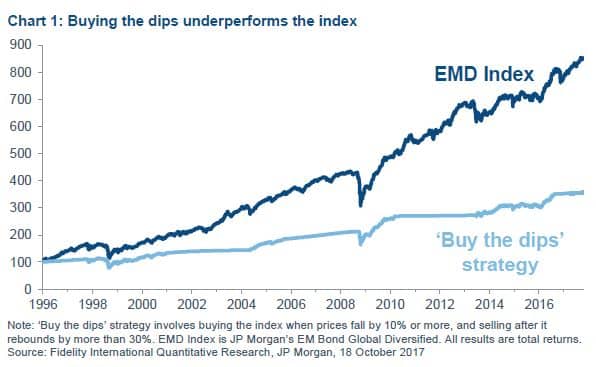

We tested the ‘buy the dips’ strategy over nearly 22 years and found that the underperformance versus a continuously invested strategy was stark (see Chart 1).

While buying the dips does reduce the extent of drawdowns, the reduction doesn’t translate into any improvements in the Sharpe ratio.

In fact, the strategy’s Sharpe ratio is significantly worse than the continuously invested index approach.

In setting our ‘buy the dips’ strategy, the underlying idea was to time the market to reduce the drawdown but participate in the upside when markets recover.

Both the required drop and the required rebound need to be large enough (5 per cent or more) to avoid excessive turnover.

The strategy does better when the rebound is bigger than the initial drop, and it also benefits from the receipt of coupons in addition to price recovery.

The results

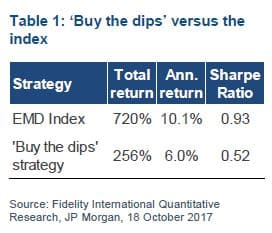

Using a required drop (D) of 10 per cent and a required rebound (R) of 30 per cent, the strategy is dominated by the index across total return, annualised return and the Sharpe ratio (table 1).

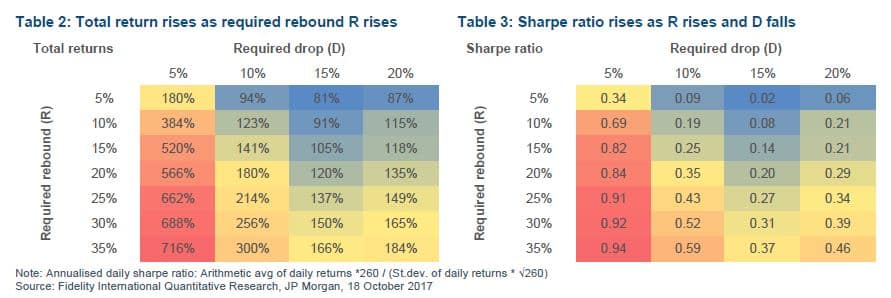

As expected, the total return and the Sharpe ratio increase as the R increases because exposure is only taken when R is higher (Tables 2 and 3).

If we change the D, we find that both total returns and the Sharpe ratio fall as D increases – there is an inverse relationship between D, and total return and the Sharpe ratio.

This is the crucial point: we can only hope to match the index total return and Sharpe ratio when the required drop falls to around 5 per cent and the required rebound is above 35 per cent.

This renders the ‘buy the dips’ strategy effectively useless for long-term investors because with a low required drop, investors will still have to invest at the most troubling times (when markets continue to fall before reaching the bottom), and the high required rebound means that investors will need to spend longer in the market but without simply remaining in the market continuously and reaping the rewards of staying invested.

It’s the worst of both worlds: anxious down markets without the benefit of continuous market exposure.

Conclusion

The risk and return characteristics of buying the dips in risky fixed income markets such as EMD depends on how much certainty is required before buying.

Waiting for a deep drawdown means it is likely that the strategy will remain in cash for extended periods. While this can be very successful in making large returns once a decade, the aggregate performance over the last 21 years averages only a third of the long-only strategy.

Buying smaller dips increases the time spent exposed to the market and pushes up returns, but investors still have to contend with further drawdowns as the market searches for the bottom, and the strategy lags the total and risk adjusted returns of remaining exposed to the market.

The Sharpe ratio of the buying the dips strategy can approach the index result, but only when the required drop is low and the required rebound is high (i.e only when the strategy starts to be exposed to the index for long periods), but it still fails to match the total returns of being fully invested long-term.

In short, the ‘buy the dips’ strategy can only hope to match the risk and return profile of the index when the required drop is low and the rebound is high.

This means that investors are in the market for long periods without the rewards of staying continually invested, and they face further drops as the market finds it bottom.

EMD is a volatile asset class and it’s natural for investors to try to improve risk and return characteristics by tactically trading it.

But the numbers do not indicate there is value in such an approach. In fact, investors are penalised for reducing time spent in the market and rewarded for staying continually invested.

The best strategy is to remain in the market and allocate effectively within it.

Marton Huebler is head of tactical quantitative research at Fidelity International.