Alternative beta is a good example of this, where a lack of clarity has resulted in misconceptions about this type of investment strategy.

To many investors, ‘beta products’ simply offer returns around an asset class or benchmark.

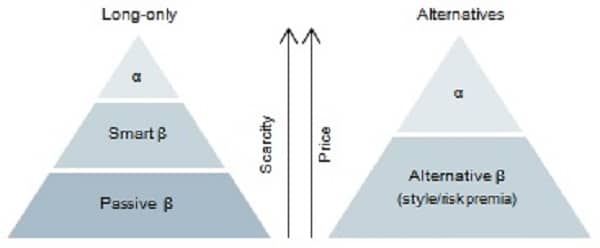

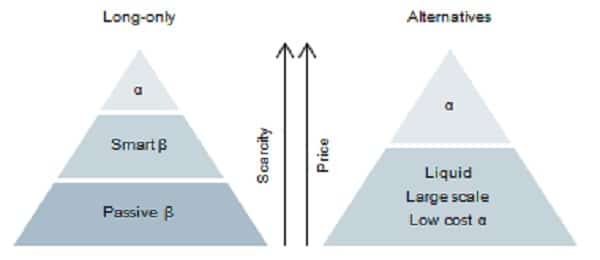

As the diagram in Figure 1 illustrates, passive beta replicates a pre-defined benchmark index (e.g. iShares MSCI World) and smart beta expresses a factor tilt within that universe (e.g. iShares Edge MSCI World Value), leaving alpha as the scarce skill of generating additional returns.

But while this model is generally applicable to long-only strategies, it is unhelpful when thinking about alternative mandates.

Figure 1. Alternative beta’s perceived place in the investment universe

Alternative investment strategies use long and short exposures to exploit inefficiencies in markets.

These inefficiencies are known as style or risk premia; examples would include the convergence between stocks with high and low book valuations.

As indicated in Figure 1, it is tempting to group these approaches under the ‘alternative beta’ umbrella to mirror the established classification model applied to traditional assets.

However, this does not work in practice. While we believe it is appropriate to associate alternative beta strategies with larger capacity, higher liquidity and lower fees, they are not ‘beta’, since seemingly similar strategies realise significantly different returns.

This article outlines the difference between traditional and alternative beta, and explores the variety of factors which drive the dispersion of observed performance.

We argue that alternative beta is not really ‘beta’ at all.

Traditional vs alternative beta

The case for traditional beta is well established and intuitive.

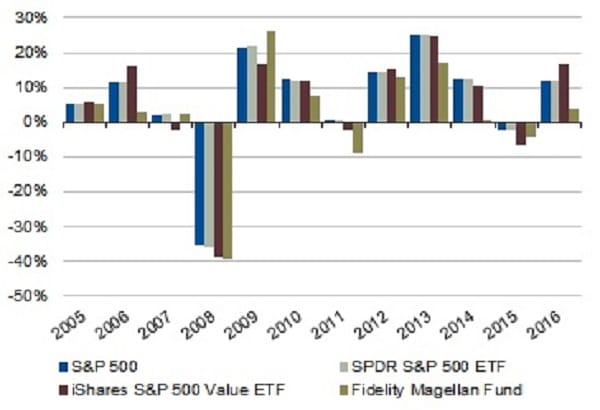

As Figure 2 illustrates, long-term performance of investment strategies (active and passive) is influenced heavily by broad market direction.

It is little surprise that many investors look to passive strategies to achieve core asset class returns, and therefore that they would seek products labelled ‘alternative beta’ to essentially provide them with passive hedge fund exposure.

It is here that the misnomer becomes problematic.

Figure 2. Traditional beta – annual performance of three funds versus S&P 500

What’s in an alternative beta strategy?

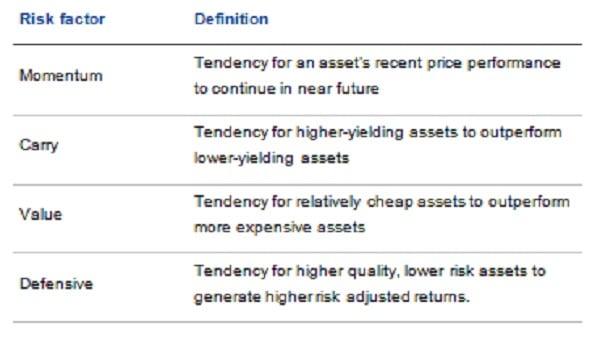

The risk and style premia on which alternative strategies are based are difficult to categorise.

Figure 3 shows a range of risk factors that describe key investment styles.

Figure 3. Alternative risk factors

The performance of strategies with common risk factor labels can be very different, however.

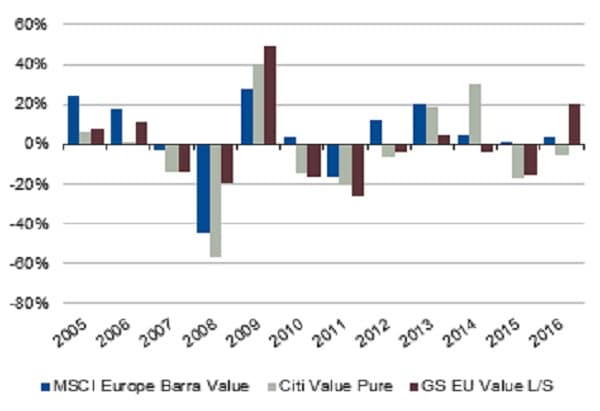

Figure 4 compares three market neutral value strategies investing in European stocks: they each have similar objectives, but very different outcomes over time.

Figure 4. Annual performance of value risk premia

Indeed, as we will see later, an examination of portfolios categorised by any of these factors normally shows a broad spectrum of performance, making these imprecise labels for comparison.

So how are these differences in outcomes explained? Is there a case for alternative strategies having beta sensitivity to any appropriate benchmark?

To answer these questions, we must consider three key choices available around an alternative strategy’s construction: parameters, conditioning and execution.

Parameters

A strategy’s parameters are its trading principles.

These include decisions like investment universe, metrics for measuring risk factors and lookback periods for interpreting data.

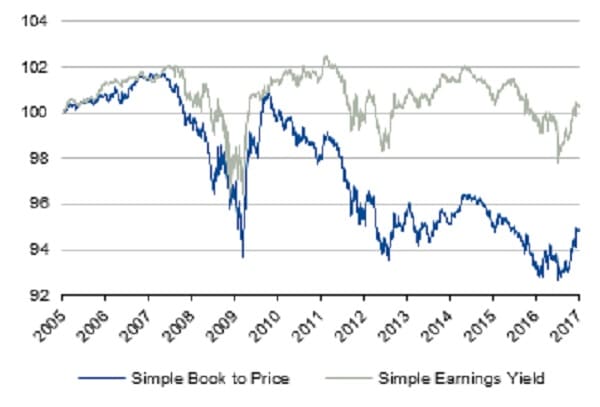

To understand the potential impact on returns associated with these parameter choices, consider a European value strategy and compare its performance using two different valuation metrics: book-to-price and earnings yield.

This is illustrated in Figure 5, which shows that changing even one parameter can lead to a substantially different return path.

Figure 5. Interpretations of European value – simulated performance since 2005

Conditioning

The second set of choices relates to conditioning, or the rules that nuance the implications of parameters.

Examples include risk management techniques, methods of weighting constituents based on their factor signals, or introducing secondary signals.

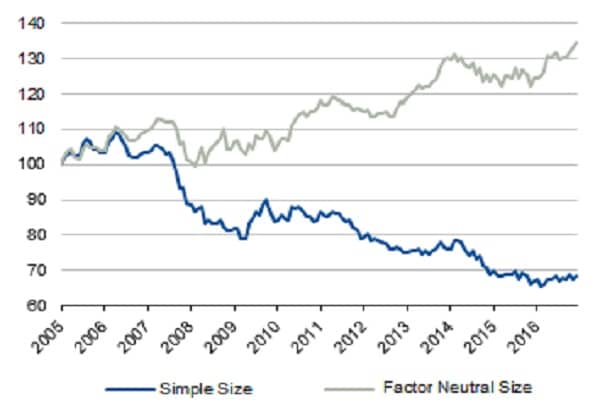

The impact of varied conditioning is shown in Figure 6.

This illustrates two methods seeking to capture the size risk premium – the premium paid for taking the risk of owning small cap stocks, relative to the wider market.

CFA textbooks, Fama/French and the pantheon of mainstream financial academics will tell you that there is a premium for investing in smaller market capitalisation stocks.

Interestingly, however, Figure 6 shows us that a naive method of portfolio construction may be deficient in delivering the expected returns.

Figure 6. Simulated portfolios capturing size risk premium with varied conditioning

Execution

Constructing an investible portfolio strategy naturally requires decisions around execution.

This requires striking the balance between purity of signal and the cost of turnover in the context of market movements.

The parameters and conditioning of a portfolio may be robust, but can quickly degrade if rebalancing is too sporadic.

Alternatively, if turnover is too frequent, this can result in spiralling transaction costs, compromising realised return.

Conclusion

Ultimately, ‘alternative beta’ has a specific meaning, which is different to the traditional definition of beta.

The nature of alternative markets makes benchmarking inherently difficult, and the active choices involved in constructing a coherent alternative factor strategy amount to something more like the specialised skills we associate with generating ‘alpha’ returns.

There are some investment product properties that the word ‘beta’ should automatically bring to mind.

It should imply higher liquidity, larger capacity and operational efficiency, which in turn should also imply a lower fee than a fully-fledged alpha seeking product.

All these properties are achievable in practice for alternative strategies, so we would propose to amend the schematic shown in Figure 1, to that illustrated below in Figure 7.

What some see as ‘alternative beta’, we view as a cheaper, larger-scale, more liquid, alternative alpha.

Figure 7. Alternative beta is liquid alternative alpha

Simon Savage is the director of alternative beta at Man Group.