In this increasingly “dammed if you do, dammed if you don’t” world, identifying and treating greenwash is becoming an essential survival skill for businesses. The greenwash critics want it both ways. They want businesses to be vocal about what they’re doing but are also poised to persecute any violations. So this raises the question, how to identify and navigate these threats?

The concept of greenwashing needs no introduction. What may be less appreciated is that over time, it has created several sophisticated permutations for us to navigate. Non-profit financial think tank, Planet Tracker, has pointed to a greenwash “hydra” (taken from the many-headed serpent in Greek mythology), summarised as:

- Greenwishing: setting legitimate (headline grabbing) targets while lacking the ability to achieve them.

- Greencrowding: seeking a collective “halo effect” by pointing to industry actions, but without acting themselves.

- Greenlighting: highlighting green credentials in order to shift attention away from damaging activities.

- Greenshifting: shifting the blame up or down the business value chain to other parties.

- Greenrinsing: continuously moving sustainability targets before they’ve been achieved.

- Greenhushing: Under-reporting or being non-transparent on sustainability data to avoid scrutiny.

While awareness of these subtitles is interesting, what are the consequences?

Regulation’s rising

Until recently, Australia has taken a relatively muted approach to regulating “sustainable finance”. However, a major landmark was drawn in December 2022, with Treasury issuing a consultation regarding mandating climate-related financial disclosures for key segments of financial markets. Essentially, the paper outlines key considerations in designing a standardised, internationally aligned framework for disclosure of climate-related financial risks.

There are big implications here for thousands of businesses. Transitioning to an increased burden of reporting will be a challenge. However, it’s worth remembering that this is hardly unprecedented when dealing with company financials. It’s been more than 50 years since a worldwide standardised system of financial reporting was established, and now these international standards are the norm with increased comparability significantly benefiting stakeholders and investors.

One of the key phrases Treasury uses here is “internationally aligned”. This is not by chance. Globally, regulators have agreed that to mitigate greenwashing and develop meaningful sustainability disclosure standards, maximising interoperability of these standards will be key. Inevitably, this means that Treasury’s proposals won’t be the last we see. Developments in other jurisdictions like the EU, the UK, and the US are shaping disclosure in other jurisdictions. Disclosure in public markets will trigger more disclosure in private markets. Businesses that may be out of scope of reporting mandates will be increasingly captured by value chain reporting. The short version is that players in the financial system are rapidly running out of room to hide.

Risky business — Greenwashing in Australia

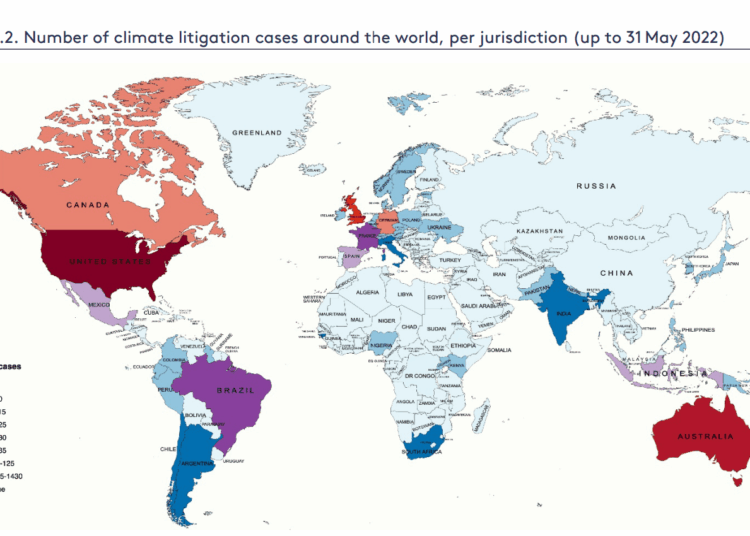

At face value, greater interoperability of standards is a step forward in the fight against greenwashing. However, as can be seen below, litigation is also on the rise. Globally, there are over 2,000 cases of climate change litigation alone currently underway. And while more than half these cases are in the US, Australia is currently sitting in second place with over 120 cases.

Number of climate litigation cases around the world, per jurisdiction (as at 31 May 2022)

Source: Global trends in climate change litigation: 2022 snapshot, Setzer J, Higham C, London School of Economics

Greenwashing threats are very real, as are the consequences. Both the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) have identified investigating greenwashing and taking enforcement action as key priorities for 2023. In 2022, ASIC warned that it was switching from education to enforcement on greenwashing, and has also noted that a next step for infringements may be civil court proceedings and penalties “significantly in excess” of those in infringement notices to date. This was highlighted by an announcement in February 2023 that ASIC had launched proceedings against a noted superannuation fund, for alleged greenwashing conduct.

The ACCC noted last year that globally, estimates from consumer protection groups put the level of false environmental claims at 40 per cent. In response, the ACCC have begun sweeping the internet to identify claims that “set off alarm bells”.

While better regulation and guidelines will help, unfortunately it’s not always that simple. The world is messy, ambiguous and nuanced. Issues are complex and multi-faceted. It’s not always about right versus wrong, sometimes its right versus right from two combatants with incompatible ideals.

With the stakes getting higher, how should we react? Is there a way to cut though the noise and confusion?

How to cut through and identify potential greenwashing

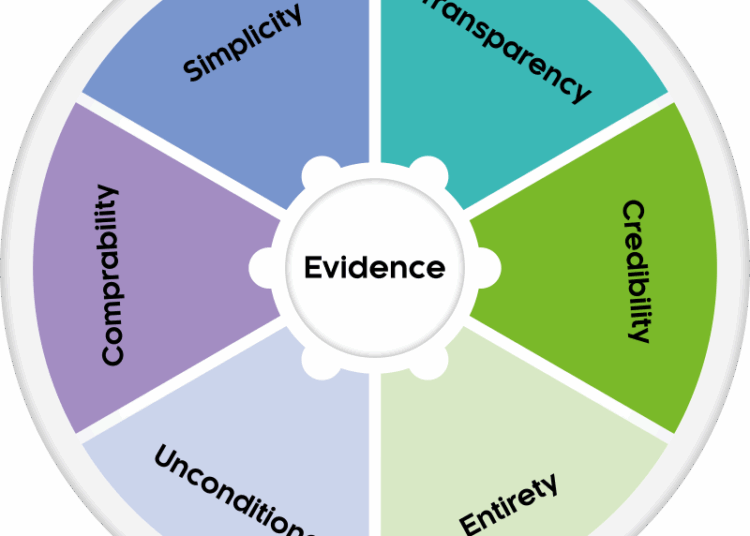

With so subject to potential greenwash allegations, is there a way to simplify the problem? As a researcher, I believe in the saying “claims without evidence can be dismissed without evidence”. When putting a choice through the greenwashing test, you need to consider, where is the evidence to back a claim? While there are a series of supporting issues to consider, backing claims with evidence is a foundational concept.

How to test potential greenwashing? I suggest you ask yourself the following six questions:

- Is a claim transparent, accurate, and clear to ensure an informed choice?

- Is there current, credible evidence to support the claim?

- Does it tell the entirety of the story without obscuring the other parts of the overall impact?

- Is the claim unconditional, or does it contain partially correct or incorrect aspects or apply conditions? If there are caveats, are they transparent?

- If comparisons are used, is their basis fair, accurate, and clear?

- Are claims simple enough to be understood and assessed?

A greenwashing example — how to show the full picture

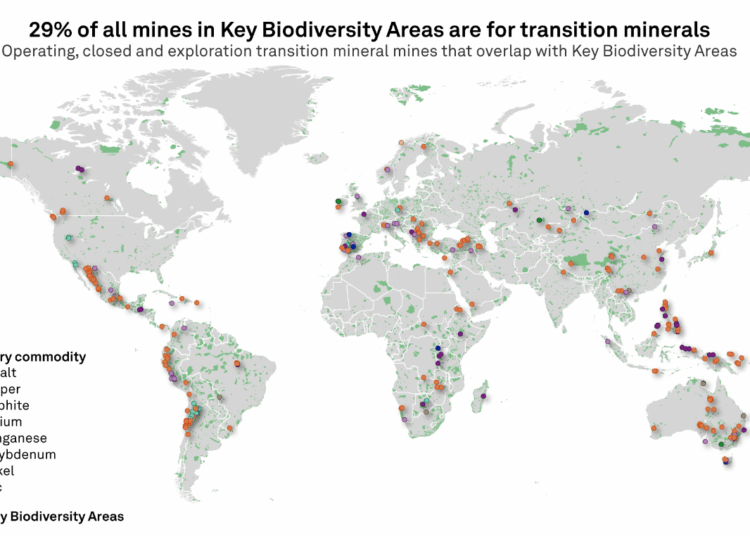

How would we use this test in practice? Not all greenwashing is merely doing one thing and saying another. It can be more subtle. Let’s use the transition to a low-carbon economy as an example. At face value, low-carbon technologies are a necessary part of the move to a more sustainable future. But if a fund was to focus exclusively on the benefits of low-carbon technologies, this would potentially not tell the entire story (#3 above).

What’s wrong with this picture? According to recent research, 29 per cent of global mining sites for energy transition minerals lie within key biodiversity areas. Mining could place pressure on the biodiversity, undermining the resilience of these ecosystems and their role in addressing climate change. Other issues like human rights violations and water use are also common issues to plague mining these minerals.

Source: S&P Global

This example shows the potential of a greenwashing allegation if the focus of the fund was exclusively on the positives and did not reflect the impacts as a whole given the reliance on biodiverse environments and other issues. It’s important to acknowledge risks and challenges.

Assessing a fund is a multi-disciplinary endeavour. The best way forward is to understand the basis on which claims are made and supported as it is an essential part of evaluating a fund, and not something limited to understanding greenwash. Testing and understanding greenwashing is not an easy feat and requires an approach that is both broad and deep.

While it’s vital for managers to be able to measure and demonstrate the role of RI in their investment strategies, we believe it’s equally important that investors can accurately identify which strategies meet with their needs and align with their investment beliefs. Our RI framework and other tools helps advisers and their clients understand the integration of a manager’s responsible investment themes into their processes, and exploring deeper themes in the portfolio.

Dugald Higgins, head of responsible investment and sustainability, Zenith Investment Partners