The key problem is that the idea of holding commodities as insurance against rising prices is flawed. In general, the buyer of insurance (or a put option) pays an upfront premium in return for guaranteed protection against losses on the covered asset. But when buying commodities to hedge against inflation, the investor faces both substantial principal risk and, at the same time, the desired pay-off is not guaranteed.

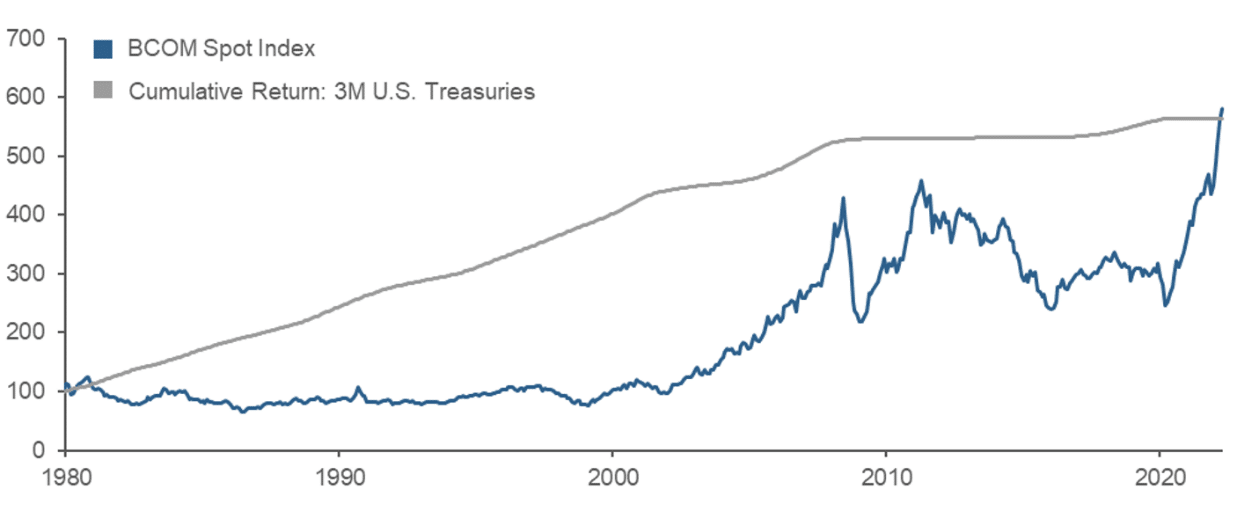

One way to illustrate this is to look at the Bloomberg Commodity (BCOM) Index, which tracks the prices of 23 broadly diversified futures contracts on physical commodities. It has returned around 7 per cent over the past year. But tracking the index back as far as 1980, we can see that it has essentially matched the returns from holding cash, as shown below. Similarly, in CPI-adjusted terms, the spot price of gold is roughly flat compared with where it was in 1980.

Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index versus Cumulative 3-Month Treasury Returns

Sources: Acadian based on BCOM Spot Index data from Bloomberg. BCOM Spot Index and Treasury returns indexed to 100 as of 31-Dec-1979.

This chart also highlights another aspect of the longer-term risk connected with buy-and-hold commodity allocations. Commodity prices may experience large and extended swings, often described as ‘cycles’, associated with protracted supply-and-demand imbalances in the underlying physical markets. Across different commodities, the size and length of such cycles reflect the capital expenditure and time required to bring new supplies online — as well as shifts in demand patterns and the availability of close substitutes, among other factors.

The investment risk associated with these cycles is clearly evident in this chart. The BCOM Spot Index’s rise in the decade prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and its decline in the following decade trace out global supply and demand imbalances associated with the acceleration and deceleration of China’s growth over the period.

For an investor who had been sitting on a long-only commodities allocation as an inflation hedge, the recent surge in prices might offer some validation, but that run-up followed a painful decade that saw peak-to-trough price declines on the order of 50 per cent across the commodities in the index.

Cost of carry

Also, establishing and maintaining long exposure to commodities involves a form of risk not associated with pure financial assets. In the case of commodities, the investable instrument is typically a futures contract or other derivative, the returns of which include carry, which on the one hand reflects financing costs and the costs of storing (or otherwise maintaining consistent exposure to) the underlying physical commodity.

Over the long term, the average impact from these costs of carry has been fairly modest. As a first-order measure, returns to the BCOM Index, which reflect excess returns from buying and rolling futures and thus carry, have trailed returns on the BCOM Spot Index by about 20 basis points annualised since 1980.

In the commodities boom that preceded the GFC, for example, the carry paid long futures holders handsomely, but it became a material headwind as the cycle reversed.

The carry will also vary across different commodities and, in some instances, may become quite large. For example, while natural gas price levels have not exhibited a consistent trend over the past 20 years, an investor who had gained exposure to natural gas through rolling futures starting at the turn of the millennium likely would have virtually nothing left of the initial investment as a result of persistently high carry costs.

Drawbacks of simple active hedging strategies

In trying to mitigate the risks and the opportunity cost of buy-and-hold commodity allocations, simple forms of timing or selection may fail to capture the desired benefits. For example, an investor who had flipped into gold over the past couple of years to hedge inflation might well be quite frustrated now.

A reason for this is that this round of inflation is partly commodity-driven. As inflation trended higher, gold has dramatically underperformed oil, industrial metals, softs, and grains — commodity sectors whose prices have been driven up far more than gold by a combination of factors, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, COVID-19 disruptions, supply constraints and rebounding global demand.

Perhaps even more surprising, gold has actually sold off as inflation expectations have soared in recent months.

Looking across a broader time period, it is possible to see that while the price of gold is certainly influenced by inflation expectations, it is more closely associated with real interest rates. The near mirror-image relationship between them reflects the notion that gold can be thought of as a zero real-yielding asset, which implies that when real interest rates rise or fall, gold becomes less or more attractive to hold.

As a result, active positioning in gold should reflect not only inflation expectations but also the drivers of nominal interest rates (as well as other factors, like the strength of the US dollar, in which gold is denominated).

A better way to view commodities

The shortcomings of simple commodity-based inflation hedges point to two constructive implications. First, the objective of commodity investing shouldn’t be limited to protecting against inflation. Instead, it should include alpha generation and overall portfolio diversification. Second, the implementation of commodity investing requires a richness that is consistent with those broader objectives as well as the heterogeneity and complexity of commodities.

To be specific, commodity return forecasts should reflect not only inflation but many other drivers as well. Relevant themes include supply and demand in the physical market, central bank policy, the cost of carry, and the outlook for the US dollar or other relevant currencies.

Rather than static long-only allocations or crude timing, we would advocate dynamic long-short positioning over the cross-section of commodities. This reflects the view that commodities are regularly mispriced relative to one another, owing to the complexity of their price drivers and market segmentation. Long-short positioning can also be used to optimise exposure to carry rather than blindly assuming the associated risk or long-term drag.

Finally, investors need to bear in mind that risk relationships among commodity sectors — energy, precious metals, industrial metals, softs, and grains — will vary with the evolving economic and financial context. So does the ability of different commodities to help diversify stock and bond holdings. As such, commodity holdings should be determined jointly with those of other assets, based on dynamic risk forecasting and framed by overall portfolio risk and return objectives.

Commodities can work in a diversified portfolio

The attention drawn to commodities by the current bout of inflation certainly has positives. We believe that commodities can add meaningful value to a diversified multi-asset portfolio that goes beyond providing a simple inflation hedge.

Current conditions underscore that the drivers of commodity returns are diverse and complex. Embracing that messy reality provides a source of real opportunity in these markets.

Michael Ponikiewicz and Thomas Dobler, portfolio managers, multi-asset class strategies, Acadian Asset Management