Fixed income has always deserved a meaningful allocation in broad investment portfolios. Not only have bonds provided solid returns, they have been a source of diversification, typically rising in value as riskier assets declined. This role is seemingly challenged in our new ultra-low interest rate world.

Bond returns are traditionally more stable than most asset classes, stemming from the certainty of the nominal return if held to maturity. It is possible to earn more in return than this initial yield to maturity over interim periods, of course, if rates fall and capital appreciation is realised. But to fulfil this higher return, the holder must sell the bond. If not, the return in subsequent periods must be lower than the initial yield to maturity.

For example, a 10-year German Bund will yield -0.6 per cent if purchased today, and the cumulative return if held to maturity over this 10-year period will be -5.8 per cent. To earn more than this, returns must be pulled forward, either by transferring returns from the later years or relying on negative yields moving even lower. But just how much room is left in this “pull it forward” trade? As yields move to zero, the capacity for bonds to post high nominal returns over the medium to long term has disappeared. As potential returns suffer, so too does their role as a portfolio diversifier.

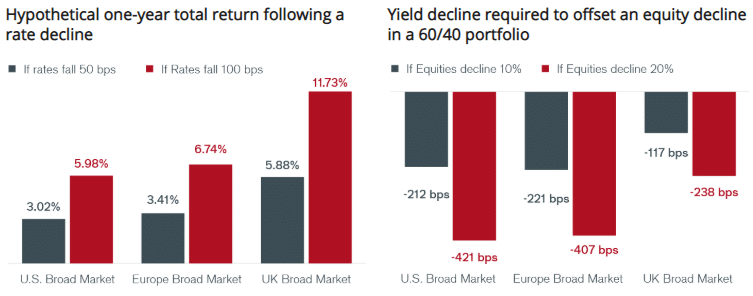

Bonds have posted strong returns over the last 12 months, with certain aggregate indices returning over 10 per cent. But as the above example illustrates, this does not portend strong future returns, except perhaps over shorter term time horizons. To see what bonds might be able to deliver in a soft economic environment, we look at what returns are possible from today’s starting point in the chart that follows.

Source: Janus Henderson, Bloomberg Barclays Indices, Yields as of 1 October 2019

Note: Yield declines represent the drop required to achieve zero return. Yield declines are shown in basis points. Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01 per cent, 100 bps = 1 per cent. Indices shown are ICE Bank of America Merrill Lynch broad market indices for the US (US00), Europe (EMU0) and the UK (UK00). Examples assume an immediate drop in rates/equity indices and are calculated using current duration and yield for the indices. Examples assume US index duration of 6.01 years and yield of 2.15, Europe index duration of 6.8 years and yield of -0.05 and UK index duration of 11.8 years and yield of 1.01. The examples provided are intended to illustrate how varying current yield and duration could impact total return. Examples are hypothetical and not based on, or a projection of, actual performance, markets are dynamic and there are many other factors that will occur which are not considered. Actual results will vary.

Bonds can still produce attractive returns, but it may require new record-low interest rates and a pull forward of returns through capital appreciation. However, with a lower “income” component, returns will be more muted, making historical returns for the asset class poor indicators of the future. This has important implications for their role in diversified portfolios. Consider what a 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds might do in a recession. If equities fall by 20 per cent, in my view, bond yields in aggregate will be hard-pressed to fall by more than 75 basis points (bps) globally or 125 bps in the US, resulting in poor returns in a balanced portfolio of equities and bonds. And with each lurch lower in yields, the picture for future returns becomes even more challenging. While their role as a diversifier has diminished, bonds still have their place in broad portfolios. Investors must adapt by:

• Accepting lower returns – most likely on bonds and other assets

• Clearly defining the desired outcome of their fixed income products

• Understanding the nuances of fixed income products, sectors and risk factors

Lower credit spreads also portend a shrinking probability of strong returns. In crisis years such as 2008, some strategies exhibited as much of an equity bias as a fixed income bias. This wasn’t as damaging for high-quality portfolios as rates had room to fall even as credit spreads widened. This is no longer the backdrop, and capital losses from credit will likely be more painful.

Take an outcome-oriented approach

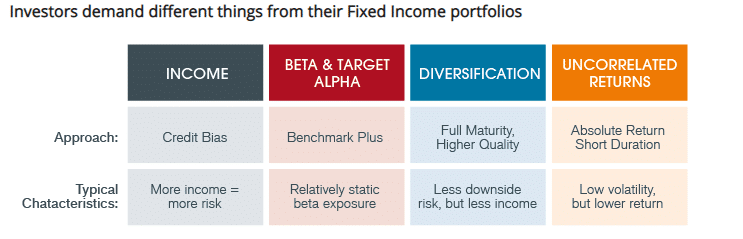

Investors need to identify the role of fixed income in their portfolios. We find that investors demand different things from their portfolios.

Bond fund allocators have traditionally made choices of “income vs portfolio diversification” strategies, or a choice of “safe core” portfolio vs “risky satellite.” Ultra-low yields make these simplistic definitions less meaningful. As the evidence in countries such as Japan and Germany indicates, most investors find negative yields intolerable, leading to a more nuanced approach. Today’s investors seek income but with better defined downside protection.

Income strategies rely on yield, which is in scarce supply today. These products will likely experience positive correlations with equities if exposures to high yield and emerging markets are elevated. Some clients seek out beta of a particular asset class. Others seek the diversifying qualities that bonds have traditionally offered. Finally, some investors want low volatility, protection from rising rates, or perhaps genuinely uncorrelated returns.

Alpha compares risk-adjusted performance relative to an index. Positive alpha means outperformance on a risk-adjusted basis.

Beta measures the volatility of a security or portfolio relative to an index. Less than one means lower volatility than the index; more than one means greater volatility.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Diversification and hedging ability

A good diversifier is not the same thing as a good hedge. Diversifiers reduce volatility, which applies to a standalone bond portfolio or to a bond strategy within a multi-asset portfolio. A hedge, on the other hand, requires a negative correlation. A robust bond hedge is one that goes up in value as other risk assets are going down. This leads to the following points:

• As a portfolio hedge, protection levels from bonds are close to their weakest in history; this reflects low or negative starting yields

• Bonds remain a good diversifier, and still serve an important role in a portfolio

First, bonds offer lower volatility than other asset classes. The inclusion of bonds in a broader portfolio of equities, bonds and real estate reduces overall portfolio return volatility. Second, low but positive correlations still permit bonds to act as a decorrelator in portfolios. Bonds will not be perfectly synched with other risk assets. They may still exhibit negative correlations in some environments. Investors can also choose to allocate to higher quality areas of bonds, seeking to maximise the odds of a negative correlation outcome.

Portfolio theory is clashing with human behavior on the subject of diversification. Low rates encourage more risk-taking and selling of high-quality bonds to buy riskier assets. Moreover, this “portfolio shift” is exactly the outcome central banks are pursuing through quantitative easing. But there are limits, and this will occur when valuations become severely stretched.

The portfolio theory response to a combination of high valuations on risk assets, coupled with poor hedging ability from “safe assets,” leads to a simple conclusion – investors should de-risk portfolios and accept unexciting returns. This is unlikely to happen willingly. Central banks are trying too hard to prevent it, and investors are loathe to forego return. Like most cycles, this is likely to end badly.

Know your bond strategies

Investors must know what their bond portfolio will do across different environments. Bonds and credit spreads have been rallying for most of the last decade. This has created a false impression that many fixed income products can do it all with limited downside. But the “beta tailwind” may no longer be with us.

There are several tools for assisting in this decision. One is the outcome focus. Two, an investor can perform due diligence on a range of managers, seeking to understand style, factor biases, risk tolerances and other metrics before committing. Both of these options are fraught with difficulty. They are labour-intensive and require much data and time to properly analyse.

A third approach is to place bond strategies in specific categories. Morningstar, Lipper and several investment management associations create categories to aid fund selection. These have proven immensely popular as a means of understanding underlying strategy.

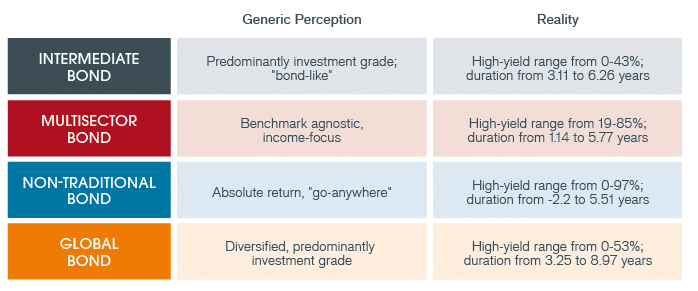

The categories are in some cases meaningful, but others much less so. Categories are robust if they group participants playing the same game and targeting similar outcomes. Large deviations in portfolio characteristics, as shown in the “reality” column of the following exhibit, can be appropriate if they represent active views. The evidence, however, suggests these deviations are more likely to reflect different outcome focuses, investment approaches and risk tolerances. Managers within the same category display radically different approaches to downside protection, and markedly different factor exposures. A top-ranking manager may be truly skilled, or they may simply be playing a different game. A low-rate environment has forced many to stretch for yield within their category, further blurring these distinctions.

Fund categories have long been embedded in the fund selection process – particularly in the US – and this will not wane anytime soon. They provide a useful starting point. But those seeking to truly understand the role of their fixed income assets will need to go a few steps further.

Bond strategy categories

Categories created to aid investors in product selection often mask the radically different approaches managers can adopt within each.

Source: Morningstar, as of 8 October 2019

Notes: Intermediate bond includes Intermediate Core and Intermediate Core Plus categories. Global Bond includes World Bond and World Bond-USD Hedged categories. Data is for the fifth and 95th percentiles to exclude outliers; actual ranges may be more extreme. Duration ranges are average effective duration for the categories named. High-yield ranges are based on calculated results and include non-rated bonds.

Play smart offense; play smart defense

High-quality bonds should still be able to generate attractive short-term returns in a risk-off environment, largely for the same reasons they have been doing so for many years. Such a move, however, will require even more negative yields, and will do nothing to combat the poor long-term prognosis.

Lower prospective returns will not prompt investors to abandon bonds. An asset class that produces positive but unexciting returns in a bear market is a desirable outcome. It is a far better option than owning more of an asset that goes down. Moreover, high-quality bonds provide a consistent diversifier, a critical component in risk management. Bonds, as a critical asset class, are as important as ever.

Today’s environment will require a heightened focus on what type of bond strategy to employ. Investors must understand both the target outcome and the path for getting there. Active managers today must make it clear how their products will deliver this outcome in a risk-adjusted manner. They should expand opportunity sets to allow for more choices of diversifiers, and they must focus on portfolio construction. The yield cushion is gone, and the costs of mistakes in fixed income will be magnified.

Jim Cielinski, global head of fixed income, Janus Henderson