The landscape for investing in emerging markets over the past six months has benefited from a more dovish US Federal Reserve and signs of stabilisation in China’s economy and capital markets.

A weaker US dollar and the related broad-based rebound in global commodity prices has seen a strong recovery in many of those emerging markets which had previously suffered the heaviest outflows.

Despite these broad trends, we believe that we must continue to be selective. Different economies have different sensitivities and will react differently to global shifts.

We will also be watching how Brexit will echo across the globe and what effect it will have in emerging markets, particularly those close to the EU.

We previously discussed our preference for economies that are natural extensions of developed markets, such as Mexico and Hungary, which benefit from growth and activity in the US and the eurozone, respectively.

The local currency bonds of these countries scored well, according to our compelling forces framework of valuations, fundamentals and market price behaviour.

In Hungary, for example, lower inflation and a slower expected growth path had encouraged further central bank policy easing which boosted the attractiveness of these bonds at the beginning of the year.

Valuations at the front end of the yield curve, particularly within the two- to four-year part of the curve, where positioning had been structurally short, appeared attractive in relative terms.

Despite the adjustment to a slower growth path, Hungary’s economy has been underpinned by strong domestic consumption and exports, particularly to the rest of Europe and Germany.

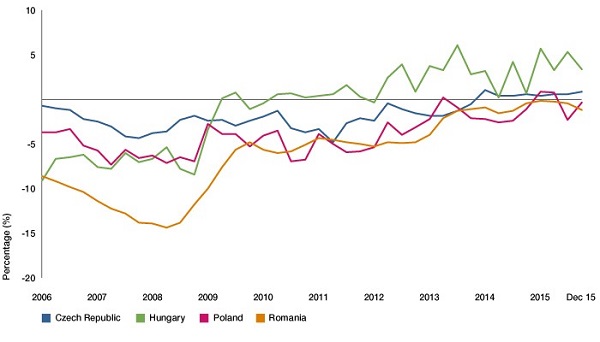

A positive credit rating outlook was also supported by its current account surplus – which is the largest in Eastern Europe, as Figure 1 below shows – and Hungary has since managed to regain investment-grade status from credit ratings agency Fitch Ratings, with the other major ratings agencies expected to follow suit.

The emerging-market universe is a disparate one, offering a wide range of investment opportunities. While there are some unifying factors, the year ahead is likely to continue to be characterised by continuing divergence between markets.

This will present us with some fundamental challenges, but also some pockets of value that are better than we have seen for some time.

A tale of two powerhouses

At a high level, emerging markets are caught between the twin economic powerhouses of the US and China. While it has been this way for many years, the exact nature of those influences has changed over time.

Many emerging markets, particularly commodity exporters, have been hit by the sharp fall in demand for basic materials and commodities from China.

As the People’s Republic rebalances its economy to favour services over heavy industry and infrastructure, fixed-asset investment and property have slowed from 25 per cent year-on-year growth to 15 per cent today.

We consider that these rates are likely to slow gradually over the medium term, rather than declining precipitously, as China works through capacity overhangs in many industries.

Nonetheless, for countries that relied on extracting natural resources and selling them to China for their economic growth, this slowdown has come as a distinct economic shock and continues to hold back growth.

For many emerging markets, the US has shifted from being a strong demand and export driver through its consumption of their products, to a monetary driver as they import its ultra-low, quantitative easing-driven interest-rate policy.

In some cases, notably in Asia, this cheap money-fuelled excess credit growth has allowed companies much freer access to global capital markets.

If, as we expect, interest rates begin to rise in the US, those economies with high debt loads will be vulnerable over the coming year.

To combat the impact of a US rate rise and to maintain competitiveness, these countries are likely to let their currency weaken against the US dollar and cut interest rates.

Different pressures

However, not all countries face the same pressures. Countries that have substantial current account deficits, such as Brazil and Colombia, and which were the primary beneficiaries of quantitative easing between 2009 and 2013, are the most exposed to the impact of rising interest rates.

Banking systems with high loan-to-deposit ratios and open capital accounts will also likely come under strain.

The key risk for 2016 is, therefore, related to the financial cycle, particularly in Asia, where debt build-up is leading to the instability of the financial system and its attendant risks, even though the risk of global recession remains very low.

Our favoured markets are those of countries including India and Hungary that continue to adopt market-friendly growth strategies, remove obstacles to do business effectively, tame inflation and gain credibility.

Natural extensions

We also favour economies that are natural extensions of developed markets, as noted above, where we cited the examples of Mexico and Hungary.

Both of these countries benefit from their neighbours’ recovery in growth and activity. The relatively robust US economy, propelled by an increasingly confident consumer, provides a potential broader benefit to Mexico.

The previous stage of US growth, powered by manufacturing and the shale oil boom, by its very nature did not pass through demand to emerging markets.

However, a more typical recovery, with consumers assisted by easier lending standards and a buoyant housing market, could see a stronger source of demand.

Nevertheless, fundamentally, those countries that were reliant on natural resource revenues – which couldn't mine it fast enough, and then couldn't stop mining it fast enough – are distinctly out of favour with investors.

Some of these commodity producers may now be fair to good value. However, even then we have to differentiate between those economies that have exhibited the deep political problems associated with a struggling economy – Brazil, for example – and those that are simply adjusting to a slower growth path.

Divergence brings back value

It is easy to be pessimistic about this challenging macro scenario – indeed, our central case remains another year of growth disappointments – but value has come back as relative and absolute valuations now more accurately reflect growth prospects.

With 150 countries, US$7 trillion in market capitalisation for the MSCI Emerging Market Index and $3.25 trillion of investible debt (according to JP Morgan in March 2015), the emerging market universe is significant and its divergence, in terms of what is on offer, is huge.

Assets invested in emerging markets have proved sticky as institutional investors continue to make strategic allocations and to rebalance fixed-income mandates.

The breadth of opportunities offered by the divergent bottom-up trends offers great scope to look for attractive returns and for value among the still fundamental challenges.

The investor’s challenge is to discriminate between the value and the value traps.

Michael Spinks is co-head of multi-asset and Investec Asset Management